The prototypical image of western professionalism does not map neatly onto minoritized bodies. To circumvent this, and to enter white-dominated domains, people of colour must transcend the dominant cultural narratives they exist in. This is all the more true in the case of individuals in highly visible positions who will face scrutiny from a white public.

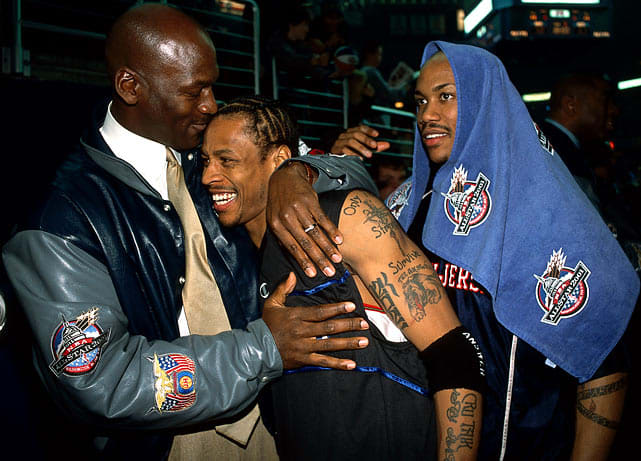

his airness transcending blackness

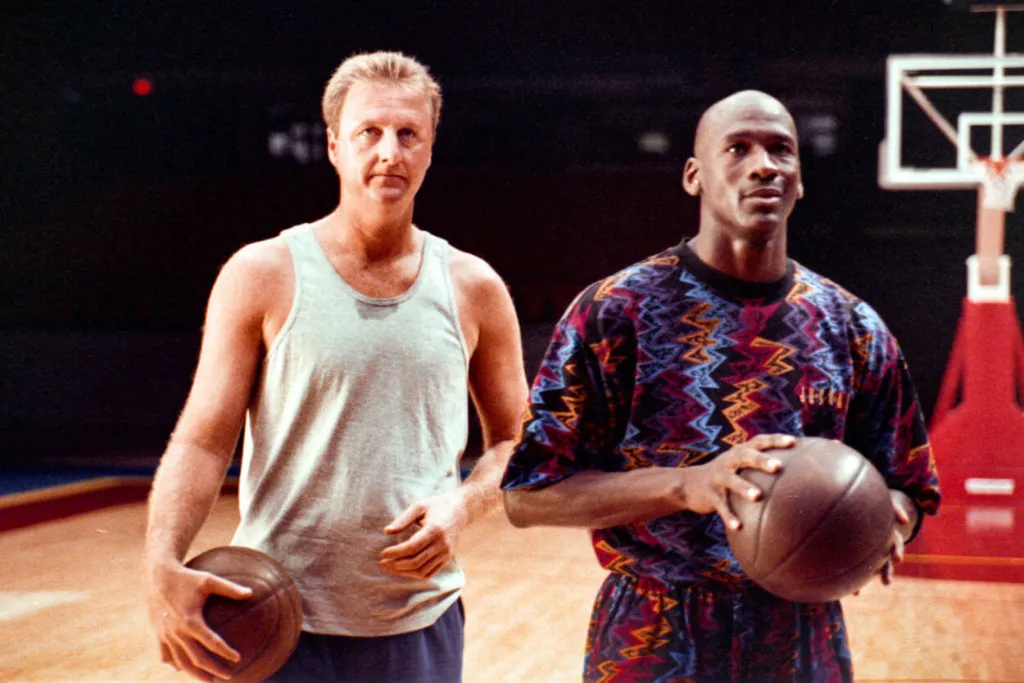

The NBA has historically been faced with the challenge of marketing a ‘sanitized’ black product to white viewers for entertainment consumption [1]. This was easy when the supremely marketable Michael Jordan was the face of the league. Even during his early playing days, Jordan was the All-American, more so than even Larry Bird, his legendary (white) contemporary.

Jordan’s then-agent, David Falk remarked that: “In the age of TV sports, if you were to create a media athlete and star for the ’90s—spectacular talent, midsized, well-spoken, attractive, accessible, old-time values, wholesome, clean, natural, not too Goody Two-shoes, with a little bit of deviltry in him—you’d invent Michael. He’s the first modern crossover in team sports. We think he transcends race, transcends basketball” [2].

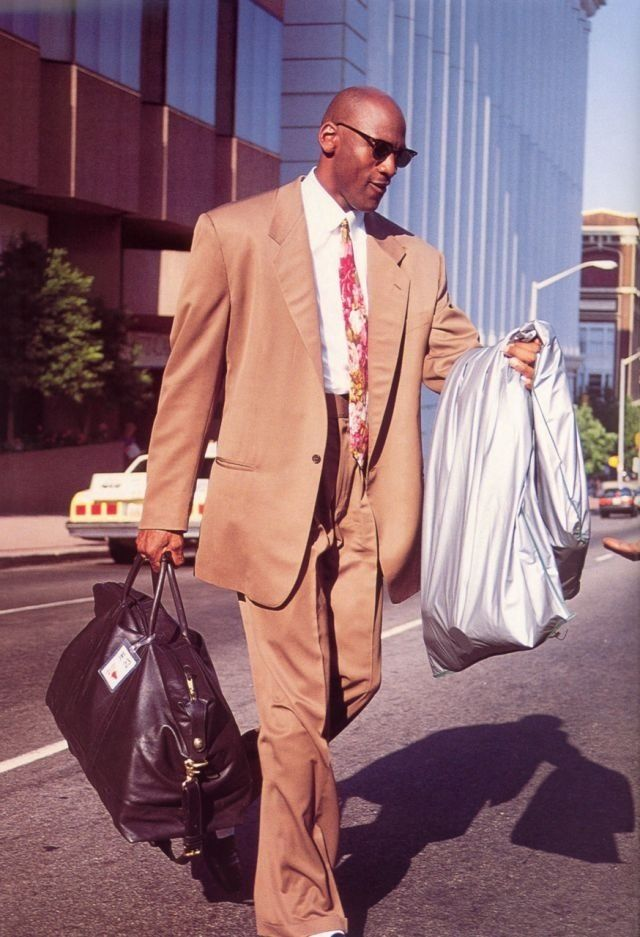

Jordan was black. In the same Raeganite, colourblind breath, Jordan was seen as a bastion of social mobility, racial tolerance, and the meritocratic American dream. With an image carefully managed both by himself and his marketing directors, Jordan would quickly become the post-racial poster boy of the league. Jordan tactically traded away his ‘baggy sweats’ and his ‘Brink’s truck worth of jewelry’ for bespoke suits [3]. Nike’s early commercials featuring Jordan had him contrasted with Spike Lee’s “somewhat troubling caricature of young, urban, African American males” [4]. These commercials would tacitly downplay Jordan’s blackness, presenting him instead as the commanding, yet wholesome All-American.

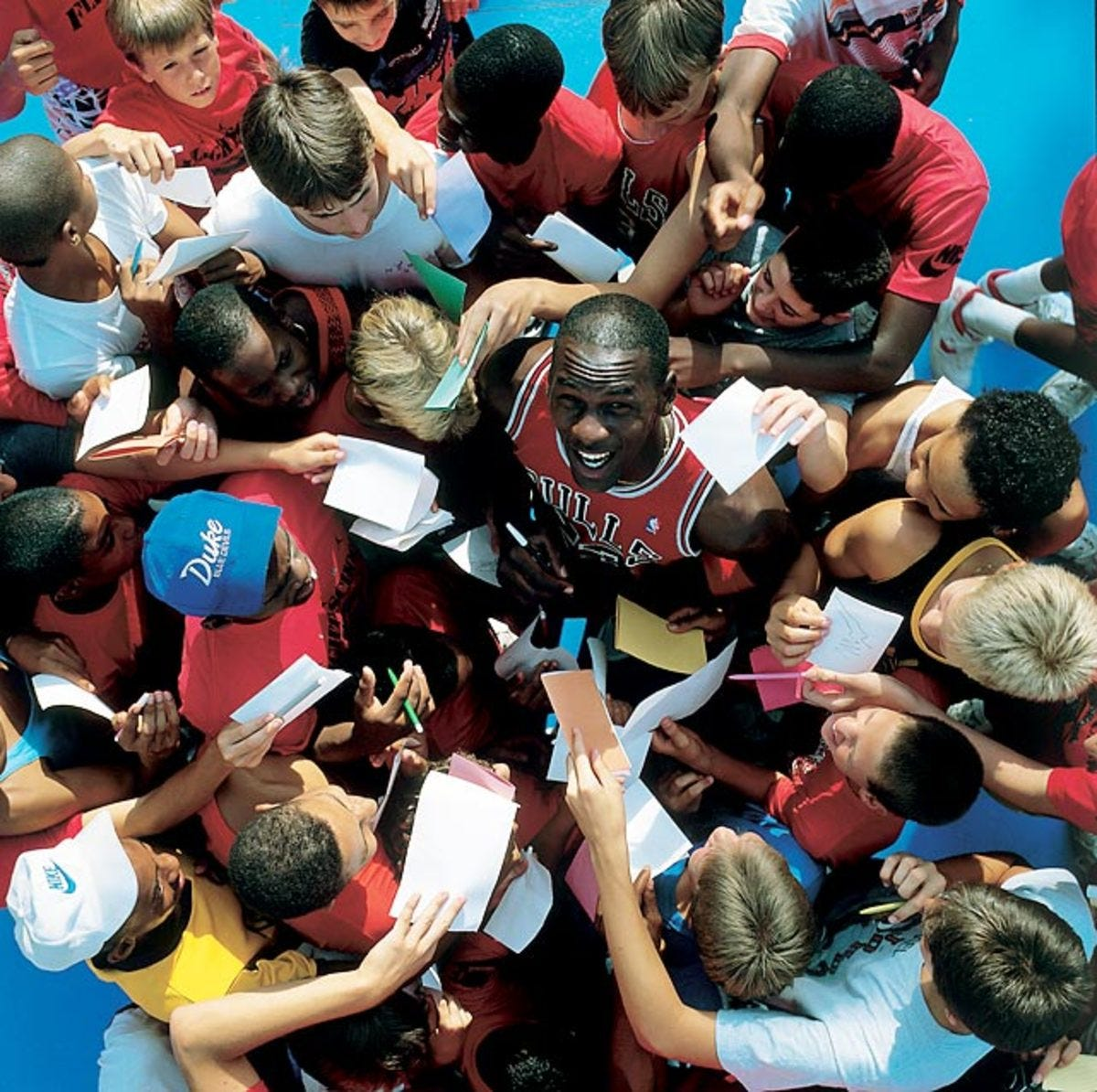

Jordan’s image was “distanced from the racial signifiers which dominated popular representations of African American males” [5], which made it so that he was “the kind of [non-threatening] figure who goes down easily with most Americans” [6]. Sports journalist Rick Telander commented that Jordan had “so carefully nurtured his image as the all-American role model that he refuses to go anywhere, get into any situation, that might detract from that image” [7]. All at once, white viewers and corporate America fell in love with their race-transcending superstar. Per Falk, the frenzy grew to such heights that Jordan had at one point turned down $300 million worth of deals in the span of four months [8].

In an effort to preserve his brand, Jordan had always been decidedly apolitical. Jordan’s notably absent voice “would have carried tremendous weight” in Chicago [9], a city plagued by issues of racial inequality [10]. Jordan even famously refused his mother’s request to endorse Harvey Gantt, a Black Democrat from his home state of North Carolina [11]. Gantt would go on to lose his bid against Republican Jesse Helms, a notorious racist [12]. Jordan would later defend this by noting that he had donated to Gantt’s campaign - privately [11].

After retiring, activist and former teammate Etan Thomas recalled that “He mentioned an event at an all-white golf club, where of course they let Michael play, but there were no Black members, and how Michael threatened at the last minute to back out if they didn’t change their policy.” Thomas had then told Michael, “That’s something people should know and then maybe they wouldn’t be saying the things they do about you”, to which Michael responded, “I don’t do that” [13].

Throughout his career, Jordan maintained a deliberately quiet record of activism and philanthropy. Jordan knew that being too overtly associated with social justice causes would hurt his bottom line. For that very reason, he could never be an agent for change in the way that other basketball greats, like Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul Jabbar were. But in a way that only a post-racial, commodifiable black superstar could, Jordan made it so that corporate America thought it sensible to dish out hundreds of millions of dollars on black athletes.

The race-transcending status bestowed to Jordan was fleeting, as it is for all minoritized peoples. For much of the early 90s, the media ravenously tore into Jordan’s alleged gambling problem. To this day, little substantial evidence suggests that Jordan ever had a relationship with gambling that threatened his livelihood. It was simply lucrative to rope Jordan back into the dominant cultural narratives surrounding Black men in America. The media would gleefully continue “lighting him like a criminal all the while Jordan was insisting a criminal is exactly what he isn’t” [14]. Even the murder of his father was quickly sensationalized into a mystery that tied back to Jordan and his ‘deviant’ behaviour - CBS’s coverage of the story mentioned that “the killing might be connected to the family’s gambling activities” [15].

This then is the trap of any purported race-transcendence - so long as you (and all members of your social group, really) walk the tight rope perfectly, you will be tolerated. That elevated status as an equal, which so often is the product of a lifetime of careful, measured effort, is flexible. Just like Jordan was, exceptional minorities can be collapsed back into the group at a moment’s notice. Similarly, once the NBA finals were underway (where Jordan triumphed), he was once more the All-American titan. America’s darling once more.

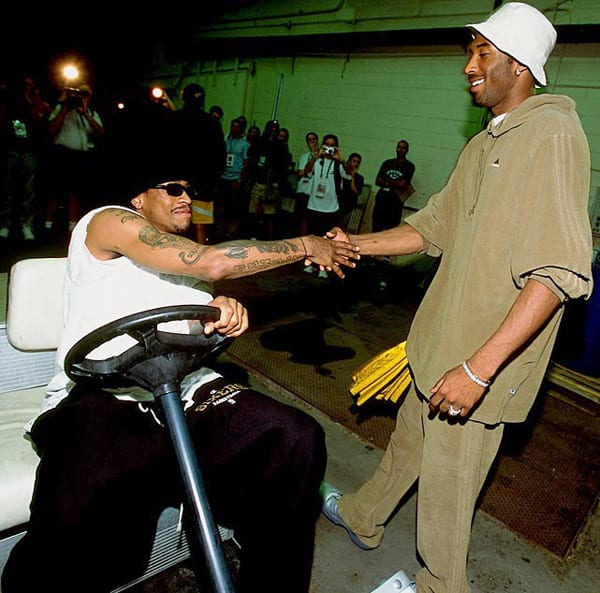

iverson, the one and only

Allen “The Answer” Iverson came from a very tough background - he grew up in the coastal Virginia area known as Tidewater, where racial fault lines ran deep and crime was ubiquitous. He was brought up primarily by his mother in a home that sometimes had no electricity or water [16]. Despite the chips being stacked heavily against him, Iverson would blossom into a two-sport phenom, soon receiving scholarship offers from major college football and basketball programs. Soon after, he would be the first overall pick of the 1996 NBA draft.

Iverson would go on to become one of the greatest guards in the history of the sport, known on the court for his incessant motor, ball-handling prowess and signature crossover move. The enduring legacy of Allen Iverson though is a product of his off-court identity.

Iverson entered his rookie season at the height of the NBA’s commercial viability [17], while the league was still under the leadership of the hard-nosed David Stern. Stern had taken the mantle as league commissioner around the same time Jordan entered the NBA.

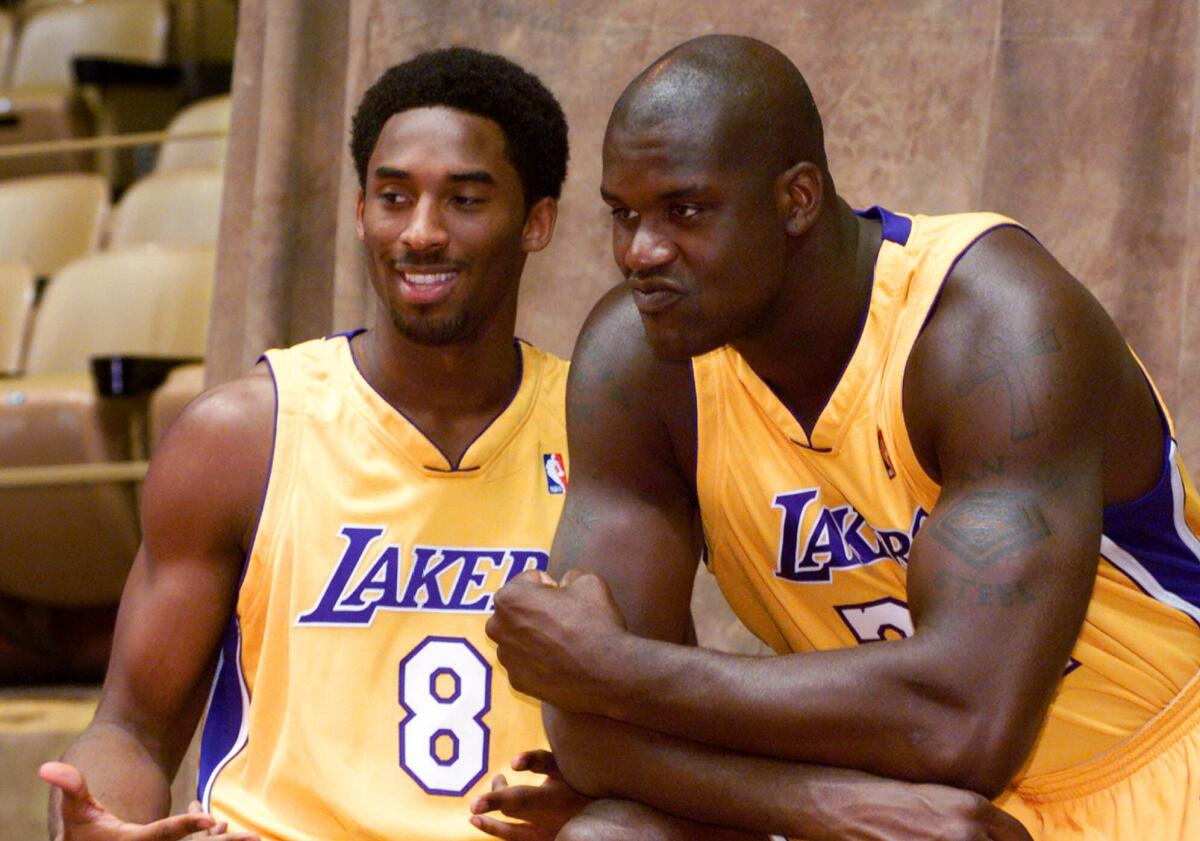

Stern’s approach of “consumer-friendliness and marketability” was exercised with great success, as league revenues had rocketed 1600% during the first decade of this informal partnership with M.J. [18] In little under a decade, the NBA had transformed it’s reputation from “a drug-infested, too-black league with dwarfish Nielsen ratings” [19] to a de facto American cultural export. The grit and finesse of basketball suddenly expressed the American ethos in a similar way to the dive of a curveball. Still, the league was scurrying to find someone to fill the lofty, colourless 13s that Jordan would soon leave behind [20].

Iverson had the requisite skill and charisma, but was in no hurry to be reigned in as the “air apparent”. On the other hand, the young and decidedly suburban Kobe Bryant loved the idea of becoming a Jordan facsimile. Kobe’s upper-middle-class status and “visibly polished” image were “more easily assimilated into the game’s overall fabric than the hip hop-inspired narrative that Allen Iverson embodies” [22]. Corporate interests felt that (white) Americans would more readily welcome the suburbanite than the “tattoos, cornrows and street persona proudly worn on the sleeves, neck and elsewhere on this former All-American out of Georgetown” [21].

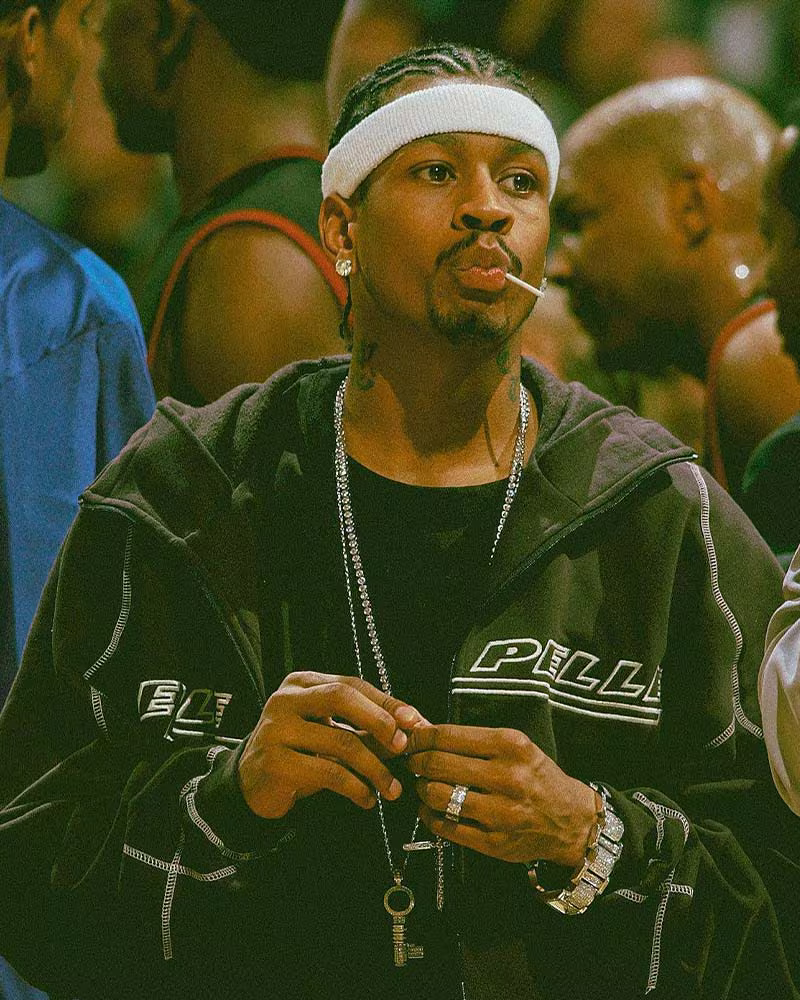

In his authenticity, Iverson challenged the status quo. Characterizing Iverson’s passive existence as a black man doing what he’d always done as some sort of active, anti-establishment activism is surely a bit misguided. However, Iverson was a young black man from the projects who had been given the chance to earn generational wealth. The league and Iverson’s critics expected some level of subservience in exchange for that opportunity. Reasonably enough, Iverson wasn’t directly grateful for the opportunity - he was there by his own merits, and the profit generation was bilateral. And so, Iverson ‘defiantly’ continued to travel with his childhood friends (who the media endearingly dubbed his “thuggish posse” [23]) and continued to wear his du-rag to his games and continued to have multiple thick, silver chains sag low on his wirey, six-foot frame.

There was a multiplicity in black identity and experience in America that was cloaked by the palatable tunes these black athletes had been forced to sing. Iverson’s authenticity set the table for successive generations of racialized players to present authentically without risk of being chastised or losing endorsement deals. The new generation of hoopers were allowed to be Black athletes, “but they were Black men first, and the NBA had to, in some way or another, reconcile all of this with their incredible basketball skills” [22].

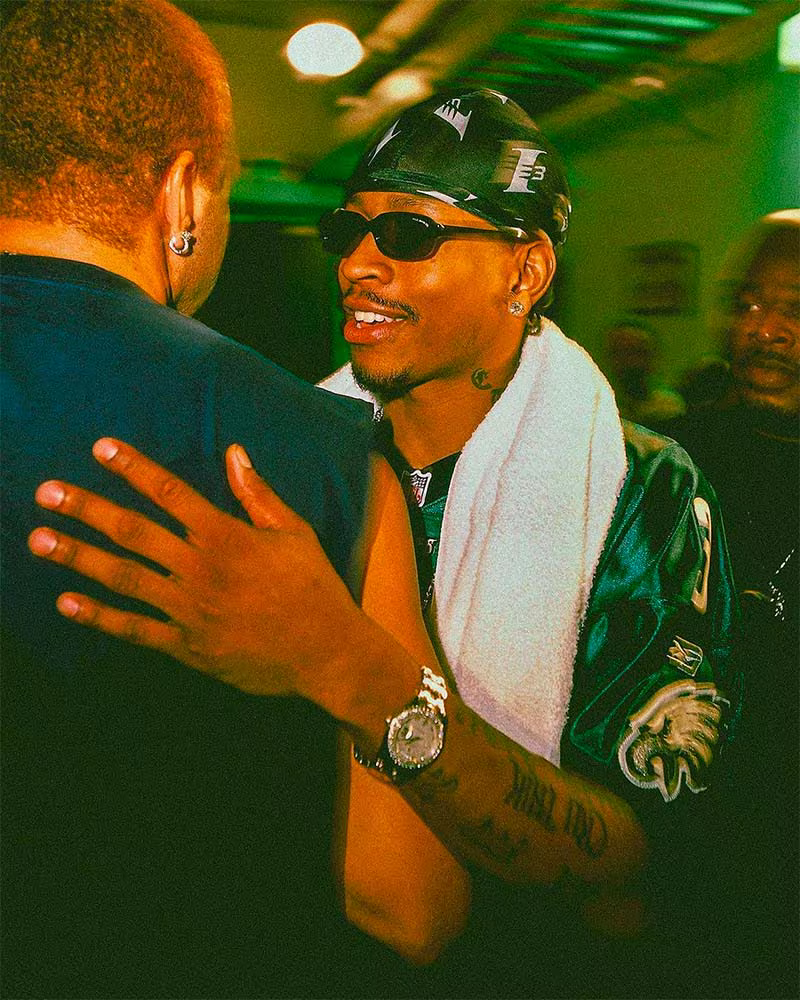

By the early 2000s, Iverson had inspired a quiet style revolution within the league. Much of the league’s black talent was dressing and getting tatted as they saw fit. Legendary big man Shaq took inspiration from A.I. when it came to getting his first tattoo [24]. Even the young King James and the tactless Tim Duncan were getting a piece of the action. Hip-hop trends were sitting courtside.

“I was the first one to do all that stuff, and I took an ass-whooping for it. […] Tattoos, cornrows, headbands, hip-hop. I never meant to start any trends. I got my butt kicked, but if that meant that the guys who came after me could be themselves, then it was worth it.” [25]

stern and institutionalized policing

This fear of losing the white consumer would boil over at the so-called “Malice at the Palace” kerfuffle, wherein multiple black players were prominently involved in a scuffle between players and fans (that was instigated by a white fan throwing a drink onto black forward Ron Artest, who was lying down on the scorer’s table). The black players, who were expected to passively accept violence at the hands of white spectators were chastised and were suspended for a year without pay, despite being cleared of wrongdoing by criminal investigations.

The NBA had a “thuggish” image problem on their hands. Commissioner David Stern couldn’t fathom the idea that the league’s image that he had so carefully engineered over the last two decades might crumble away. For fear of losing white viewership [26], and in a shoddy attempt to boost (dwindling) ratings, Stern introduced a “business casual” dress code in 2005 [27]. At play virtually whenever the player was not on the court, the dress code demanded chains, pendants and medallions be tucked in if worn at all. Sleeveless shirts, tees, headgear of any sort, sunglasses and headphones were prohibited. The most jarring inclusion was Stern’s ban on sneakers [28]. Of course, black players hardly had the wool pulled over their eyes and rightly called this out as an effort to limit black expression. Some players were calling it the “A.I. rule” [29].

The idea then was that black authenticity was not salable. Authenticity would have to be expressed via a narrow scope of sanitized, palatable blackness. The NBA, the entity that stood to profit from black bodies, was convinced that it needed to police the expression of those same bodies. By extension, the (corporate perceptions of the) white consumer base policed the image of black professionalism.

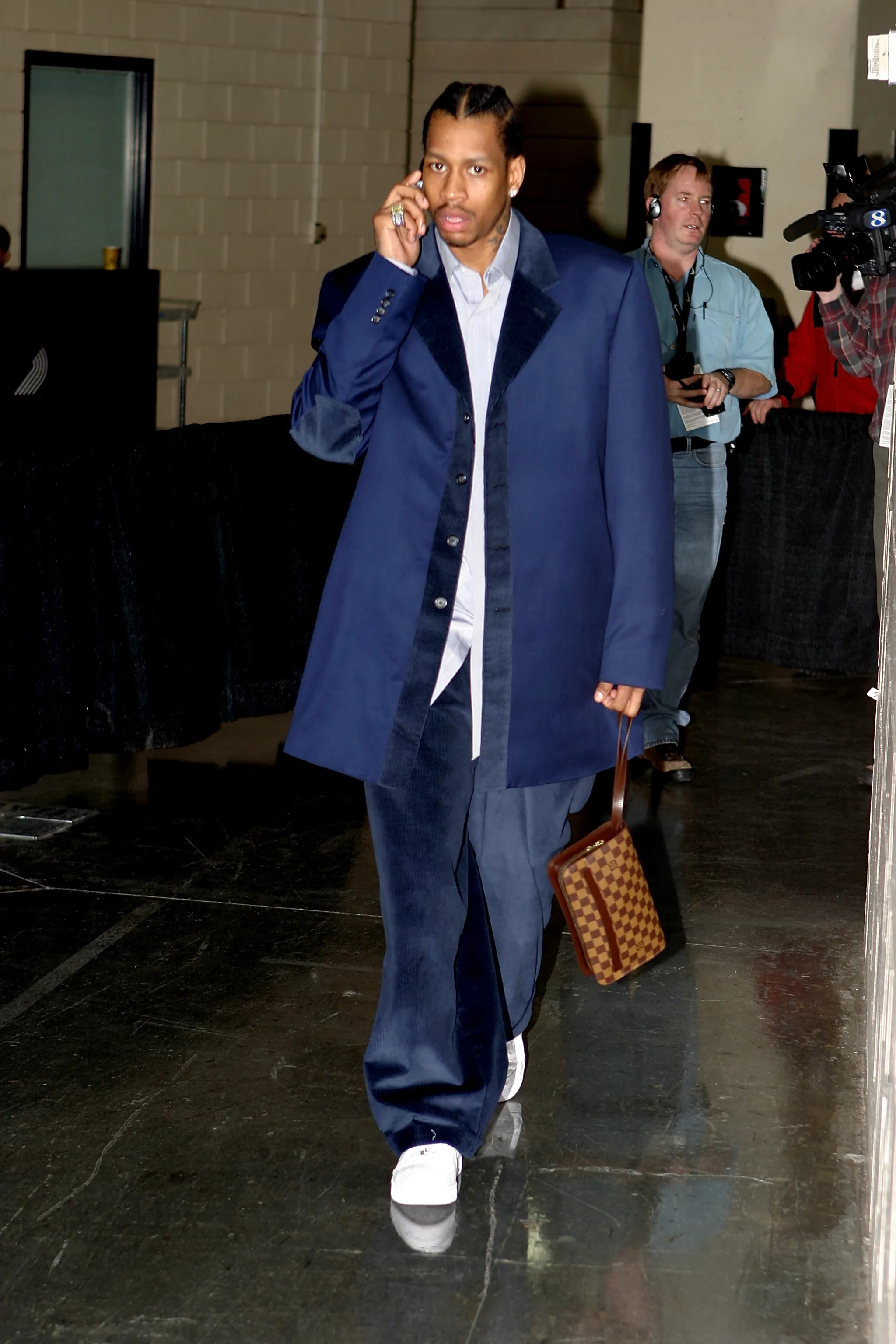

Even after this league-wide imposition, Iverson would be the one pushing the needle. Iverson would “abide” by the new dress code by leaning entirely too far into the emerging trend of oversized suits [30].

Eventually, the league would quietly phase out their dress code restrictions. This next generation of hoopers had taken from A.I. and was going to be authentic, and the league couldn’t police all of them. The modern NBA has actually become something of a haven for (certain forms of) black expression, opting not to police the opinions of black stars on black issues (quite antithetical to the NFL’s approach). Of course, this is also facilitated by the shifting demographics of league viewership [31], but the point still stands.

Talent that emerges from racialized communities often has to entertain this fickle, intersecting game of image policing. This policing is often institutionalized, but self-imposed image policing can also be a means to a lucrative end. But the modern NBA is, in large part, above this. Jordan made it so that companies saw the commercial value in investing in black talent. Iverson made it so that black talent didn’t have to be colourless.

“I love being Allen Iverson. If I die today, I want to come back and be me all over again.”

references

[1] https://www.jstor.org/stable/4539808

[2] https://vault.si.com/vault/1987/11/09/in-an-orbit-all-his-own-whether-hes-pouring-in-points-or-putting-together-business-deals-high-flying-michael-jordan-of-the-chicago-bulls-is-out-of-this-world

[3] https://www.gq.com/story/michael-jordan-suit-god

[4] https://www.amazon.ca/Michael-Jordan-Inc-Corporate-Culture/dp/0791450252

[5] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Reading-Sport-%3A-Critical-Essays-on-Power-and-Birrell-Mcdonald/7d0e77fdba46b222ec922a739647e5b11e9fcc69

[6] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/3997863

[7] https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/05/14/senseless-in-americas-cities-kids-are-killing-kids-over-sneakers-and-other-sports-apparel-favored-by-drug-dealers-whos-to-blame

[8] https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1998/03/23/washington-based-sports-agent-david-falk/ce51d504-3476-49d9-aa6c-481fb9c88ec6/

[9] https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/spectrum.4.2.01?seq=6

[10] https://www.npr.org/2021/05/06/994173342/how-systemic-racism-continues-to-determine-black-health-and-wealth-in-chicago

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2020/may/04/michael-jordan-espn-last-dance-republicans-sneakers-quote-nba

[12] https://www.motherjones.com/politics/1995/05/what-you-need-know-about-jesse-helms/

[13] https://www.the-sun.com/sport/9009728/forgotten-michael-jordan-teammate-etan-thomas-author-activist/

[14] https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/123235073/

[15] https://archive.org/details/isbn_9781555534295/page/188/mode/2up

[16] https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1996/06/16/iverson-in-transition-troubled-past-to-nba-future/f3609c58-75a8-4059-8ced-3ffd5052cbab/

[17] https://www.sportsmediawatch.com/2023/04/nba-ratings-viewership-past-30-years-analysis-where-league-stands/

[18] http://bluefieldcomp.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/102909034/466817.pdf

[19] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-03-22-tm-7431-story.html

[20] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jan-13-mn-63205-story.html

[21] https://www.espn.co.uk/nba/story/_/id/17459928/basketball-hall-fame-allen-iverson-authenticity-paved-way-today-nba

[22] https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/bison-books/9780803216754/

[23] https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/132105-iverson?tab=transcript

[24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBB8JZMTpwM

[25]

https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2476540-an-icon-at-40-the-untold-story-of-allen-iverson

[26] https://variety.com/2001/tv/news/nba-dribbles-toward-dicey-tv-contracts-1117853034/

[27] https://www.npr.org/transcripts/4971453

[28] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0193723513491750

[29] https://www.nbcsports.com/nba/news/andre-iguodala-bought-allen-iverson-suits-to-match-nba-dress-code

[30] https://www.cbssports.com/nba/news/iguodala-iverson-bought-baggy-suits-to-comply-with-nba-dress-code/

[31] https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2015/hoop-dreams-multicultural-diversity-in-nba-viewership/

addendum

originally, this piece was centered around jagmeet singh and the way the media lambasted him for carrying a versace bag. right-wing ‘commentators’ took aim at the aesthetics of politics rather than material outcomes. terribly novel phenomenon, i know, and thank heavens, most folks considered this a moot talking point. however, i wanted to analyze the issue from the lens of race, class, religion and political lines

as the writing grew, i figured i’d keep it focused on the nba. something something scope creep

more importantly, i thought it quite dishonest to transplant the unique suffering of black players in the league onto jagmeet and indians in the west. i think it’d have made sense if i really fleshed things out, and i was well on my way to doing that, but maybe that’s for another day (likely not lol)

i may as well nudge at where i was going with that though - imo, sadly, jagmeet’s public identity as a brown, Sikh, canadian man is malleable and collapsible, in the way multiculturalism often is. the status symbols he adorns himself with are partially what legitimize him in the eyes of his voter base. he’s not a champion of the working class, sure, but it’s his policies that are the tell and not his garments.

additionally, this writing is eh, alright. i like some of the prose. these references are way, way too academic probably, and i should really cite those photos. there are probably too many of them. i’ll be on that in a jiffy. or not. the pictures and clips could be more relevant, but it’s sometimes a little hard to find things from this era. i’ll hopefully patch those issues up in time.

any writing i publish from here on out will probably be less crummy - thank you for your time! x